The Last Hours of Herculaneum. When Death Came from the Mountain

Lindsey HallThe residents of Herculaneum faced a dramatically different fate from their neighbours in Pompeii during the catastrophic eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE. Whilst both towns would be destroyed, the manner of their destruction tells two distinct stories of ancient tragedy.

A Mountain's Fury Unleashed

When Vesuvius first exploded, Herculaneum seemed to catch a stroke of good fortune. The prevailing south-easterly winds carried the initial volcanic debris towards Pompeii, sparing the coastal town from the immediate rain of ash and pumice that began burying its neighbour. But this reprieve would prove cruelly temporary.

The ground had likely been trembling for days before the eruption, a warning that many residents likely heeded. When the mountain finally exploded, sending a column of rock, ash, and flame into the sky, the sight and sound must have been terrifying beyond imagination. The deafening roar, the earth-shaking violence, the towering pillar of destruction rising directly above their heads; every instinct would have screamed for escape.

The Flight to the Sea

For many in Herculaneum, the sea offered the most logical route to safety. The town's position on the coast made maritime escape seem viable, and indeed, help was on the way. Across the Bay of Naples, Pliny the Elder had launched a rescue mission with his fleet. However, the same winds and volcanic debris that had initially spared Herculaneum now worked against potential rescuers. Unable to land at Herculaneum, Pliny's ships were forced to continue south, eventually reaching Stabiae, where the elder Pliny would lose his own life to the volcano's fury.

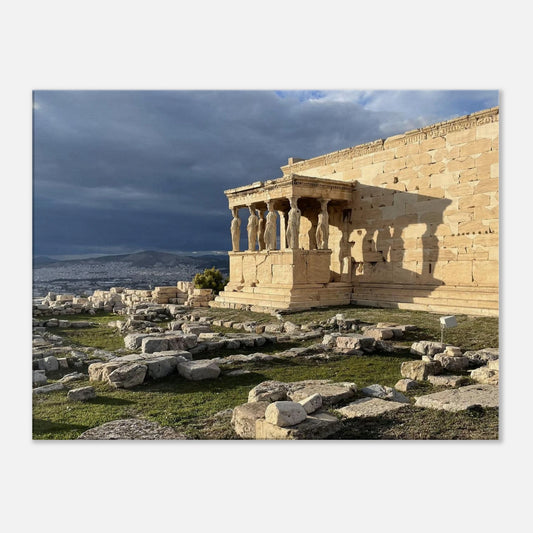

Stranded but still hopeful, the people of Herculaneum made desperate preparations. Men remained on the beach, scanning the horizon for rescue ships. A soldier, presumed to be from Pliny’s fleet, helped organise. Women and children sought what shelter they could find in the boat sheds along the shoreline, sturdy stone structures that seemed to offer protection from the falling debris and shaking ground. They waited through the day and into the night, unaware that their ordeal was about to take a far deadlier turn.

When the Column Collapsed

As darkness fell on that terrible day, Vesuvius entered a new and more lethal phase. The towering eruption column that had sustained itself for hours began to lose momentum. Twenty kilometres of superheated rock, gas, and ash could no longer maintain its vertical ascent and began to collapse under its own immense weight.

What followed was a pyroclastic flow; a phenomenon that the ancient world had no name for but would experience in all its devastating power. This avalanche of superheated gas, rock fragments, and volcanic debris raced down the mountainside. The temperature within this deadly cloud was at least 510 degrees Celsius; hot enough to kill instantly through thermal shock alone.

No Escape

The pyroclastic flow struck Herculaneum with unstoppable force, washing over the town and surging far out into the bay. The boat sheds that had seemed like refuges became tombs. The beach where men had waited for rescue became a killing field. No organic material; no plant, no animal, no human being, could survive such intense heat delivered with such sudden violence.

The skeletons discovered by archaeologists centuries later tell the story with heart breaking clarity. Families huddled together in their final moments, their bones preserving the positions in which death found them. The thermal shock was so severe and swift that many victims' brains were literally vaporized, leaving behind only the stark evidence of their last desperate attempts to shield themselves and their loved ones.

Buried Forever

The first pyroclastic flow was not the end. Wave after wave of these deadly avalanches followed, each depositing more volcanic material. By the time Vesuvius finally exhausted its fury, Herculaneum lay buried under 25 meters of solidified volcanic debris in some parts; far deeper than Pompeii's covering of debris. The flows extended so far into the sea that they permanently altered the coastline, pushing the Mediterranean back and creating new land where water had once lapped at the town's shoreline.

A Preserved Tragedy

Unlike Pompeii, where almost until the very end of the eruption victims were gradually suffocated by accumulating ash, Herculaneum's residents died instantly, their final moments frozen in time by the superheated flows. This terrible efficiency of destruction has provided modern archaeologists with an unparalleled window into the daily life of an ancient Roman town, even as it reminds us of the sudden, arbitrary nature of natural catastrophe.

The story of Herculaneum serves as a powerful reminder that in the face of nature's most violent forces, human plans and preparations often prove tragically inadequate. The sea that seemed to offer salvation became a barrier; the shelters that promised protection became ovens; the rescue that appeared imminent never arrived. In their final hours, the people of Herculaneum learned what we continue to relearn today: that the earth beneath our feet, however stable it may seem, holds powers beyond our ability to predict or control.

Picture: Taken in April 2017 at Herculaneum. These are the aforementioned boat sheds where many skeletons were excavated in the 1980's