Lucius Cornelius Sulla puts Pompeii under siege in 89BC

Lindsey HallThe year 89 BC found the defenders of Pompeii manning their ancient walls, watching with growing alarm as Roman legions approached from the north. What they witnessed was not a foreign invasion, but something far more troubling; their former Romans allies coming to crush them. The sight of Lucius Cornelius Sulla's disciplined formations advancing towards their gates marked a pivotal moment that would forever change this prosperous Campanian city.

The Road to Rebellion: Understanding the Social War

Pompeii had long been an ally of Rome, but by the late 2nd century BC, the relationship had soured. Like many Italian communities, Pompeii's citizens had grown increasingly resentful of their second-class status within the Roman system. They provided soldiers for Rome's armies and paid taxes, yet they were denied the full citizenship rights that would give them political representation and legal protections.

The breaking point came in 91 BC when the Social War (from the Latin socii, meaning allies) erupted across the Italian peninsula. The Italian allies demanded citizenship, fair taxation, and an end to their subordinate status. When diplomatic solutions failed, many communities took up arms against their former patron. Pompeii, despite its long history of cooperation with Rome, joined this bid for equality.

The Siege Begins: Sulla's Campaign of 89 BC

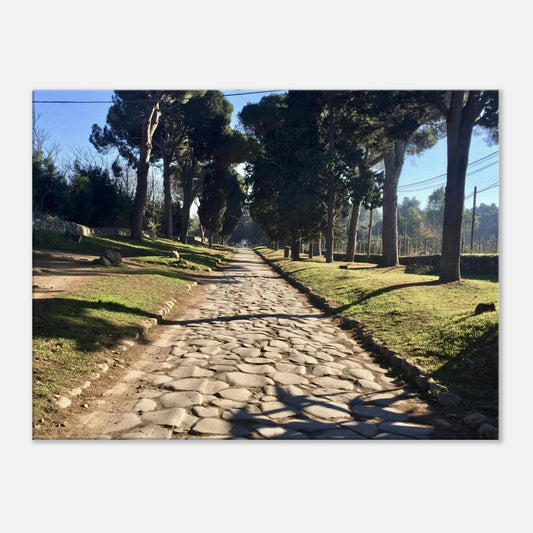

In the spring of 89 BC, Sulla approached Pompeii with his battle-hardened legions, likely advancing along the coastal road from the direction of modern-day Naples. The siege focused on the northern section of the city's defenses, particularly around the Herculaneum Gate (known in antiquity as the Salt Gate) and the adjacent Vesuvius Gate. This strategic choice made sense; the road through the Herculaneum Gate provided the most direct route to Naples and other major population centers.

Archaeological evidence still bears witness to the intensity of the Roman assault. Excavations have revealed numerous projectiles—stones, spear points, and other missiles—embedded in walls and scattered throughout the northern districts of the city. The ancient fortifications themselves show clear signs of battering, with sections of wall displaying repair work that dates to the immediate post-siege period.

Organized Resistance: The Oscan Inscriptions

Perhaps the most remarkable evidence of Pompeii's resistance comes from the eituns inscriptions discovered painted in red ochre on various walls throughout the city. Written in the Oscan script, the local Italic language of the region, these tactical markings directed defenders to their assigned positions during the siege.

The inscriptions reveal a sophisticated level of military organization among the Pompeian defenders. The fact that they could coordinate their defense through written orders suggests not only widespread literacy in Oscan but also a well-structured command system. Archaeological analysis indicates these inscriptions were hastily applied during the siege itself, showing the defenders' ability to adapt and communicate under extreme pressure.

However, despite this impressive organization and their intimate knowledge of the local terrain, the Pompeiians could not indefinitely withstand the military might of Rome's professional legions. The combination of sustained battering attacks, siege tactics, and the psychological pressure of facing Rome's most capable general ultimately broke the city's resistance.

The Fall and Transformation

The siege concluded with Pompeii's surrender sometime in late 89 BC, though the exact duration of the siege remains unclear from ancient sources. The consequences were immediate and profound. Sulla established the city as a Roman colony, renaming it Colonia Cornelia Veneria Pompei in honour of his family name (Cornelius) and his patron deity Venus.

More significantly, Sulla settled a substantial number of his military veterans within the city, fundamentally altering its demographic and cultural character. These Roman colonists brought with them Latin language, Roman law, and Roman customs. The transformation was remarkably swift; within a generation, Pompeii had evolved from a rebellious Oscan-speaking Italian town into a thoroughly Romanised community.

Legacy of the Siege

The siege of Pompeii represents more than just another military victory in Rome's expansion. It marked the end of Pompeii's existence as an independent Italian community and the beginning of its life as a Roman city. From 89 BC until Vesuvius's catastrophic eruption in 79 AD, Pompeii would develop as a distinctly Roman urban center, complete with amphitheater, Roman-style forums, and the social structures that defined Roman municipal life.

Today, visitors to the Herculaneum Gate can still observe the ancient stones that witnessed Sulla's assault. The gate itself, one of the most impressive and well-preserved entrances to the ancient city, stands as a silent testament to both the city's resistance and its transformation. The modern ropes and barriers that protect the archaeological site would indeed have proven little challenge to Sulla's engineers, but they now serve to preserve this remarkable window into a pivotal moment in Roman history.

Picture taken March 2025 at Pompeii.