It wasn’t "Fortune of This Day" for Julius Caesar

Lindsey Hall

Standing amid the ruins of Largo Argentina in Rome, near to where the Senate once met on the Ides of March, you can almost hear the ghosts of history whisper.

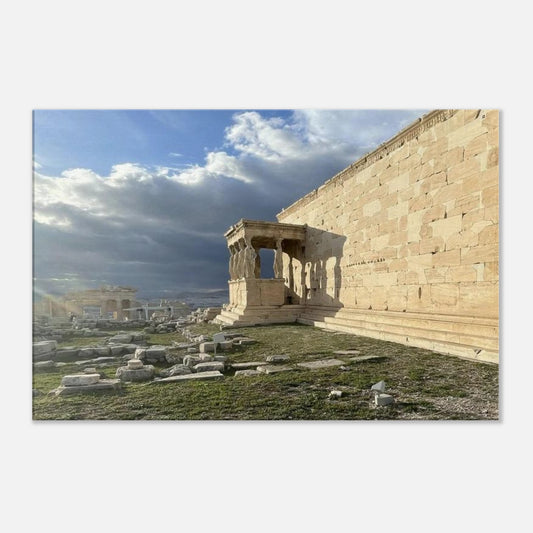

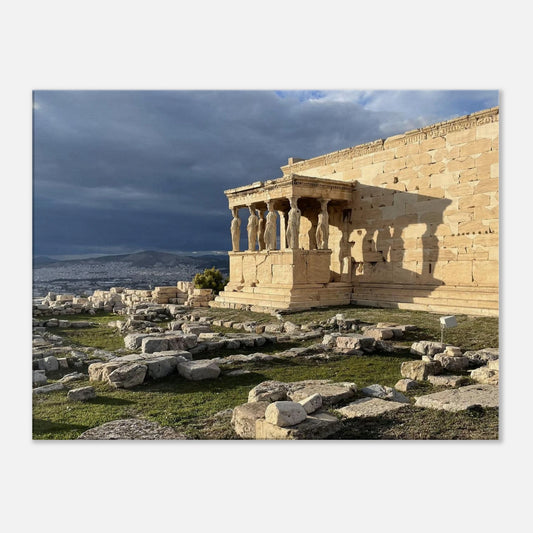

The broken columns, the ancient foundations, and the ever watchful cats offer no explanations. But what is here is heavy with meaning.

The irony of it all is almost theatrical. Julius Caesar, fresh from his rise to absolute power, was assassinated not in some remote alley but near to a sanctuary dedicated to Fortuna Huiusce Diei; “the Fortune of This Day.” A goddess meant to represent the providence of this very moment. That moment turned out to be his last.

The final walk

The day began with dread. Calpurnia’s dream, vivid and loaded with omen, had convinced Caesar to stay home. His hesitation was real. But then came Decimus, one of the conspirators cloaked in friendship, who gently mocked the idea that Rome’s greatest general should be ruled by a woman’s dreams and superstitions. Caesar changed his mind. Together they left Caesar's home and made their way toward the Curia of Pompey.

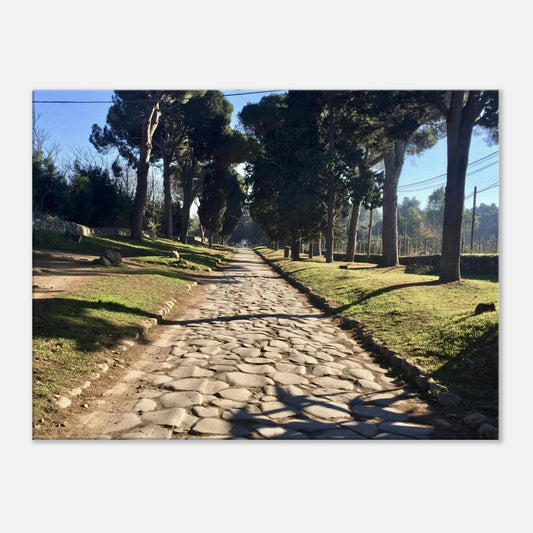

The walk was short. The area that is now Torre Argentina was once bustling; filled with temples and porticoes. They would have passed by the Temple of Fortuna. Did Caesar glance at it? We will never know. But we know what happened next.

“Et tu, Brute?”

In the Curia, surrounded by men he called friends, Caesar was stabbed twenty-three times. According to Plutarch, Caesar said little, until he saw Brutus. “Kai su, teknon?”; “You too, my child?”

This was more than a political killing. It was a ritual execution, a public cleansing of power. But it backfired. The conspirators fled Rome, the Republic they hoped to save collapsed under the weight of men who fought for Caesars legacy. And Fortuna? She moved on.

Echoes of ancient stones

As I stood there, in the sunken ruins of that sacred space, I tried to picture the scene. I tried to visualise the Curia and theatre of Pompey which would have once dominated the view, now broken beneath the streets and buildings beyond, to ancient reconstructions I had studied. A soft breeze stirred the trees above. Somewhere, a street performer’s voice echoed faintly.

The Temples of the Largo di Torre Argentina aren't marked by plaques or dedications. There are no velvet ropes, no marble bust of Caesar. You wouldn’t know what happened near here unless you’d read the footnotes of history. And yet, it feels significant.

A history that walks beside you

Visiting, and for the first time descending into the site, wasn’t just a box to tick; it was a quiet ambition and achievement. You walk on stones where sandals once trod; near to where daggers were drawn and history pivoted in a heartbeat.

You come expecting to find ruins. You leave realising you’ve met ghosts.